Course Details

Knee problems are incredibly common in dogs. Whether the dog is a top level athlete or a professional cookie catcher at home, the knee is one of the weakest links. Cruciate disease, ACL or CCL problems are undoubtely the number one reason why owners take their dogs in for a visit with a rehab specialist. In fact, knee problems are so common that chances are good that everyone with a dog is going to experience a problem with knees at some point. Osteoarthritis is a problem with many of our dogs, and this course will help you help your dog strengthen and support the arthritic area. The multimodal approac is crucial to addressing osteoarthritis and is inclusive of reducing pain and infllammation, and improving strength and range of motion.

This class is applicable to ANYONE that is concerned about their dog's knees. This class will focus on strategies to help prevent knee problems, non-surgical approaches, discuss when surgery is needed, and raise injury awareness. Our goal is to help our dogs have the best quality of life for the longest time possible.

I would strongly encourage a gold or silver level if you do have a dog with a knee problem. The gold level will allow for one on one interaction, and the homework will discuss specific exercises for you and your dog, as well as their progressions. This is also an excellent class for those involved in the rehabilitation, strengthening and training of dogs with knee problems.

Teaching Approach

One main lecture will be released each week for a total of six main lectures. Additional supplemental lectures will be released throughout the six weeks. Students are expected to go at their own pace and their dog's own pace. If there is an exercise or activity that is not benefitting their dog, or their dog is struggling with, it is expected the student will ask for assistance or skip over the activity.

Instructor: Debbie (Gross) Torraca

Instructor: Debbie (Gross) TorracaDeborah (Gross) Torraca (she/her), DPT, MSPT, Diplomat ABPTS, CCRP has been involved in the field of animal physical rehabilitation for over 17 years and currently owns a small animal rehabilitation practice in Connecticut called Wizard of Paws Physical Rehabilitation for...(Click here for full bio and to view Debbie's upcoming courses)

Syllabus

Week 1 - Basic anatomy of the knee and action of the knee and the hindlimb

Week 2 - Common injuries to the knee: cruciate injuries, patella luxations, and soft tissue injuries

Week 3- Prevention of knee injuries and the multimodal approach to stifle osteoarthritis

Week 4 - Conservative approaches to the cruciate deficient knee, and when surgery is needed

Week 5 - Programs and progressions of cruciate injuries - surgical and non surgical

Week 6 - Putting it all together - the program for your dog

Prerequisites & Supplies

No prerequisites. Suggested equipment: Infinities, rocker boards, disks, Pawds, and others. Please contact Debbie for specifics on your dog and a 10% discount code on various pieces of equipment. deb@wizardofpaws.net

Sample Lecture

Welcome to the Bum Knee Class! As dog owners, many of us have had either direct or indirect experience with a knee injury. Cruciate ligament injuries are the most common type of injury seen by an orthopedic veterinarian. Additional injuries to the knees include patellae or kneecap problems, soft tissue injuries, Osteochondritis dissecans or OCD lesions, and fractures. In the first portion of the class, we will go over some anatomy so you have a clear understanding of the knee. We will also start with some exercises this week, which will progress through the class.

A Quick Anatomy Lesson

The knee, also called the stifle, is located between the hip and the hock in the hindlimb. The major motions of the knee are flexion (bending), and extension (straightening). There are also some small rotational movements. The stifle is flexed or bent when they are in a sitting position. It is also bent or flexed when the dog is going up stairs. The stifle straightens when the dog is walking and trotting.

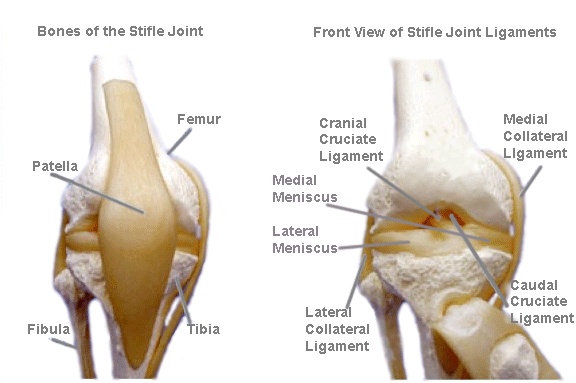

The diagram below gives you a quick anatomy lesson of the stifle and the ligaments.

There are several bones that comprise the stifle or knee joint. The femur is the large thighbone. The tibia and fibula are in the lower leg, between the knee and the foot. The tibia is the larger bone, and the fibula is the smaller bone. The patella or kneecap, the smallest bone in the area,assists with the stability of the knee and helps with action of the quadriceps muscle.

There are also several major muscles that surround the knee and help keep the knee functioning. The quadriceps are comprised of four muscles, and act to extend and straighten the knee. The four muscles are the rectus femoris, the vastus medialis, the vastus intermedius, and the vastus lateralis. The hamstrings are the large muscle group in the back of the leg, and they are responsible for flexing the knee and extending or straightening the hip. The hamstrings are usually the largest muscles in the dog’s rear. The adductors, or the inside muscles, are also responsible for stabilizing the knee. As we talk about the strengthening the knee, I will mention these muscles and what we are working on.

The video below is of some landmarks and stifle flexion and extension.

ACL/CCL/Cruciate Injuries

The cranial cruciate ligament, commonly known as the CCL, ACL or the anterior cruciate ligament, is one of the most common injuries seen in the dog. There are many reasons why dogs tear their CCL, including some predisposing factors. Some of the predisposing factors include the following: overweight dogs, active dogs, athletic dogs, hormonal components, and certain breeds. A study published in 2003 in the Canadian Veterinary Journal presented the following data: Labrador Retrievers 21.6%, Poodles 9%, German Shepherd dogs 8.5%, Golden Retriever 4.6%, and Rottweiler 4%. [i] I think these are interesting statistics, but we also need to keep in mind how popular the Labrador Retriever is! The same study indicated female dogs are more likely to rupture their CCL than male dogs – 65% females compared to 35% males.

With regard to overweight dogs, it is well documented that weight plays a key role in the development of CCL related injuries. One study indicated that the body weights of dogs with a ruptured CCL were significantly greater than those of the control dogs. In addition, dogs weighing greater than 22kg or 48.5 pounds had a higher prevalence of CCL ruptures. This greatly increased the prevalence of bilateral CCL ruptures, or the ruptures of both stifles. [ii] Because it is so important to keep your dog at a healthy weight, I will constantly discuss weight control and weight loss with your dogs.

Additional information on CCL ruptures has pointed to a decrease in incidence in intact males, intact females, or in late neutered females. In early neutered dogs, the occurrence was increased by 5.1% in males and 7.7% in females, compared to intact and late neutered dogs. [iii] There is often a significant debate on the effect of neutering and spaying on CCL injuries. We can talk the whole class about this, but I will start a thread in the discussion.

There are two cruciate ligaments in the dog – the cranial and caudal cruciate ligaments. Cruciate means cross in Latin, and that is just what these two ligaments do. The cranial cruciate ligament (also called the anterior cruciate or the ACL) prevents the tibia, or the lower leg, from moving forward on the femur, or the upper leg. When there is damage to the ligament, there is too much movement of the tibia on the femur while the dog is standing, walking, and running. The caudal cruciate ligament prevents the tibia from moving backward on the femur. This ligament is rarely injured in either dogs or people. In people, it is referred to as a dashboard injury since it is commonly injured in a car accident when the dashboard hits the lower leg and causes the tibia to move back abruptly.

With a cruciate injury, the dog will have decreased weight bearing on the injured side. The below are a series of videos of a dog with a young, active, female German Shepherd. The first video was taken in November of 2014, and she is jumping very well. The second video begins to show you the decreased push off, and jump propulsion. By the third video, her owner knew something was wrong and she was evaluated and treated for a partial cranial cruciate ligament tear. The decreased performance in agility was the tell tale. Itis always important to look at subtle changes in the dogs behavior and performance. I always assume physical before psychological.

The photos below are examples of decreased weight bearing. In some of them, you do have to look carefully to view the decrease in weight bearing.

If you have ever experienced an ACL injury yourself, or if you know someone that has, then you know that the injury is obvious immediately. I always laugh when people say they tore their ACL on their last ski run of the day. Of course it was the last ski run - they tore their ACL and probably had to be carried down the mountain! In all seriousness, though, people tear their ACL quickly and abruptly, and the injury usually drops the person to their knees. (No pun intended!)

It's a bit different in dogs, because most dogs tear the ligament progressively. The ligament starts to fray or straggle a little bit with an initial injury. That fraying causes some instability in the dog's knee, which in turn causes some pain and weakness. That can set the dog up for a further injury, and it becomes a vicious cycle of injury, instability, pain and weakness. Sometimes owners notice the dog is slowing down slightly or not pushing off the rear as well. For example, the dog's time may be slowing down in agility and his jumps are not as powerful. The dog also may not be able to jump as powerfully into the car, or run up the stairs as fast. Ideally, the owner would catch the injury at this point, but that is not always the case. If the dog continues to push through, he may tear the ligament. If the partial tear is caught early enough, there are varying opinions on treatment. Conservative treatment involves rehabilitation and controlled activities. Another approach is surgery - and there are many different techniques on the surgical procedures. We will discuss that in the next few weeks.

In fact, here are many opinions on exactly what is the best treatment for cruciate injuries. I think this is very dependent upon the owner and the dog, in addition to the lifestyle we are looking at. We have been taught that surgery is really the only option, and it certainly may be right for some dogs and for some owners. However, it may not be the right option for all owners and dogs. In one study, it was indicated, “The ideal treatment modality for cranial cruciate ligament injury has yet to be determined...”[iv] Consumers do want options on the treatment of CCL injuries. If your dog sustains a knee injury, I strongly suggest that you obtain a few opinions before deciding on the course of treatment.

Other studies have discovered that surgery does not cure cruciate disease and pointed to the fact that about half of the Labrador retrievers rupture the contralateral CCL within six months after a tibial plateau leveling osteotomy. [v] The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy is a type of surgery performed for cruciate deficiencies. Additional studies have indicated that a dog that tears one ligament is forty to sixty percent likely to tear the other one. Some studies have also indicated a higher incidence of osteoarthritis after CCL surgery.[vi]

In complicated chronic cases, the unrelenting course of CCL disease in dogs emphasizes the need to try a conservative approach first. A surgical option may be pursued at any time, but I encourage a conservative approach if the dog is not in pain. The dog's overal function should be re-evaluated every two weeks. Even in humans who acutely rupture their ACL, many physicians advocate rehabilitation initially.[vii] Strehl et al state that at present, there are no evidence-based arguments to recommend a systematic surgical reconstruction to any patient who tore the ACL.[viii] Although research for non-surgical approaches for humans and dogs are growing, there is no evidence supporting crate rest only. A combination of rest and a multimodal approach is recommended to successfully treat the CCL injury.[ix]

And while we are on cruciate ligaments, I do not want to fail to mention the other cruciate ligament - the caudal cruciate or the posterior cruciate ligament. This is not injured as commonly in people or in dogs. And in fact, it is not very common at all. However, it can happen. In people, it used to be known as the 'dashboard' injury. When a person was involved in a car accident, if their knee was up against the dashboard, the impact would push their tibia or lower leg backwards. This would injure the posterior cruciate ligament. The injury creates an instability and a need for stabilization. I have seen a hand full in dogs and they are most likely due to trauma or some odd incident. We will be bringing these up as well.

Preventing Injury

In short, CCL disease is very complicated and there may not be a quick answer to the problem. In addition, there are many reasons a dog may tear their CCL, such as weight, conformation, sex, altered vs. unalterated, age, and overall condition. We can absolutely control some of these reasons, and in this six-week class, we will work on the things we can control at this moment: weight and their overall condition. We may not be able to completely prevent an injury to the CCL, but we can stack the cards in your dog's favor.

The first step in either addressing a knee injury or preventing an injury is to examine the dog’s weight. Try to weigh your dog once a month, and keep track of the weight. And ask yourself what the realistic weight should be for your dog.

The next step will be to establish a baseline for the circumference of your dog’s thighs. By measuring and documenting your dog’s thigh circumference, we can determine how he is progressing with strengthening exercises. You can also identify problems early this way. The muscles will atrophy and become smaller if there is a problem. By measuring the thigh circumference once a month, you may be able to get a jump-start on a problem. It is also normal for one leg to be a little bit larger than the other – 1 to 2 cm. This is the same with us – our dominant side tends to be a bit larger than the non-dominant side. Right-handers have slightly larger forearms on their right side compared to the left side. In the photos below, I am using a tape measure to pick a spot on the upper leg or femur to use as a landmark. The top part is one the greater trochanter (the bony outside part of the hip), and the bottom part is on the outside of the knee. You want to pick an area approximately seventy percent up the thigh, or from the bottom. Make sure to pick the same spot on each leg. I sometimes use a piece of chalk or a Sharpie pen to make a dot on the hair. Once you have that spot, use the tape measure to measure the girth of the thigh. Try to do it a few times to practice. I usually take three measurements, and then take the average. Hairier dogs are a bit more of a challenge!

I have also included another method of measuring the legs - some of you may find this easier.

And then our final step will be to begin some basic strengthening exercises to help strengthen the stifle. We will continue with these throughout the course, but we will start with the basics this week. Our first activity will be to stand squarely on a flat surface. The dog should be able to stand for ten seconds without shifting his weight. This sounds rather simple, but if the dog is having problems with his knee, he will shift his weight off that leg. You may notice that he is not fully able to weight bear on that leg, as in the photos above. In addition, more weight will be placed on the contralateral or opposite forelimb. So if the right knee is injured, the dog will place more weight on the left forelimb to compensate. Dogs normally place approximately thirty to forty percent of their weight on their hindlimsb, and sixty to seventy percent on their forelimbs. With a knee injury, the dog will reduce the weight on the hindlimbs and place more on the forelimbs. So, while standing squarely for ten seconds is a baseline exercise, it is also an activity to determine if there is a problem.

Once the dog is standing squarely, slowly shift his weight backward by placing a little pressure on the chest. The goal is to have the dog accept some weight on the hindlimbs for a few seconds. You do not want to push so hard that the dog goes flying over. When the dog shifts his weight back, it is working on the hamstrings. The four muscles that comprise the hamstrings are so important in helping to stabilize the knee. Perform the shifting exercise until the dog is tired. You will know he is tired if the dog sits, runs away, or picks up one of the hindlimbs. This is a great exercise to perform throughout the day – two to four times a day.

The following videos are of weightshifting on exercise equipment. We will get to this- but start on the floor first!

The last exercise for this week will be asking your dog to walk backwards. This will also be an important baseline exercise for your dog. I have included videos of dogs that have never done this before. These are raw, and you can see it is not too easy of a task. The first step will be to encourage the dog to step backwards, and as soon as he takes a step back, treat and/or praise him. Dogs often default to a sit; try to catch him before he sits and take a step into the dog.

And this is of a dog that does understand the command:

And some bloopers for you!

Homework

1) What is your dog’s breed and current weight? Please discuss if this is the ideal weight for your dog.

2) Measure your dog’s thigh circumference and compare side to side. Please post a photo or video of you performing the activity.

3) Stand your dog squarely and examine if he is putting all of his weight on his hindlimbs. Ask the dog to stand for ten seconds and please video this.

4) Try the weight shifting exercises and please video. These are weight shifting videos on equipment - which I promise we will get to!

5) Begin to walk your dog backwards on a flat surface.

This is Lola. She has a partial tear on the right cranial cruciate ligament. The owner does not want to pursue surgery just yet, and is concerned about the other knee. In the photos, you can tell she is really compensating with the right hindlimb. Her right hindlimb is out to the side. This increases the amount of weight on the left hindlimb as well as the left forelimb.

One of the beginning exercises involves placing her forelimbs up on a wedge. The wedge helps increase the weight onto the hindlimbs. We will work to place the wedge under the right and left forelimb alternatively. The wedge is lovely to give a slight incline to give a gradual slope.

The next activity is placing her hindlimbs on a Disk and begin weight shifting exercises. Her forelimbs are on another disk to help increase the weight on the hindlimbs. As she begins in the photo, you can see her right hindlimb is kicked out and has decreased weightbearing. The video demonstrates the weight shifting activity for her.

[i] Harasen Greg G. A retrospective study of 165 cases of rupture of the canine cranial cruciate ligament. Can Vet J 1995;36:250–251

[ii] Budsberg SC, Flo GL, Sammarco JL. Breed, sex and body weight risk factors for rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament in young dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999 Sep 15;215(6):811-4.

[iii] de La Riva GT, Hart BL. Neutering dogs: Effects on Joint Disorders and Cancers in Golden Retrievers. February, 2013.

[iv] Au KK, Gordon-Evans WJ, Dunning D, et al. Comparison of short- and long-term function and radiographic osteoarthrosis in dogs after postoperative physical rehabilitation and tibial leveling osteotomy or lateral fabellar suture stabilization. Veterinary Surgery. 2010;39:173-180.

[v] Lineberger JA, Allen DA, Wilson ER, et al. Comparison of radiographic arthritic changes associated with two variations of tibial plateau leveling osteotomy. A retrospective clinical study. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2005;18:13-17.

[vi] Buote N, Fusco J, and Radasch R. Age, tibial plateau angle, sex, and weight as risk factors for contralateral rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament in Labradors. Veterinary Surgery. 2009;38:481-489.

[vii] Delince P and Ghafil D. Anterior cruciate ligament tears: conservative or surgical treatment? A critical review of the literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:48-61.

[viii] Strehl A and Eggli S. The value of conservative treatment in ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). J Trauma. 2007;62:1159-1162.

[ix] Harasen et al.

Testimonials & Reviews

A sampling of what prior students have said about this course ...

I have worked with a veterinary physical therapist before, but didn't feel like I had a good program to continue on at home. This class has been invaluable. My dog is moving better, and seems to be more comfortable. A good series of exercises to help her, and a good progression program to help her improve.

Learned a great deal about the working of the canine knee, and exercises needed to address issues.

Debbie was a phenomenal instructor. Extremely credible and professional, and clearly on top of her game. It was a pleasure learning from her.

Course exceeded expectations. Dr Debbie is an excellent instructor. Glad we signed up! Thank you.

The Bum Knees class had been VERY helpful to me and my Australian Shepherd. The lectures and supporting video helped me to develop an exercise program and gave me a much better understanding of what we are dealing with. Debbi was great and incredibly knowledgeable.

Duncan's gone from hiding in my room on the cushy beds to out in the house playing with the other dogs and watching the people more, and has resumed more hunting activities in the yard. He's had a TPLO and we are doing conservative management for his second CCL tear. This class has helped expand his abilities again. I hope to land a Gold spot the next time it's offered and continue building on our skills and his physical fitness. Flo. F.

Registration

There are no scheduled sessions for this class at this time. We update our schedule frequently, so please subscribe to our mailing list for notifications.

Registration opens at 10:30am Pacific Time.

CC260 Subscriptions

Gold |

Silver |

Bronze |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Tuition | $ 260.00 | $ 130.00 | $ 65.00 |

| Enrollment Limits | 12 | 25 | Unlimited |

| Access all course lectures and materials | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Access to discussion and homework forums | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Read all posted questions and answers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Watch all posted videos | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post general questions to Discussion forum | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ |

| Submit written assignments | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ |

| Post dog specific questions | ✔ | With video only | ✖ |

| Post videos | ✔ | Up to 2 | ✖ |

| Receive instructor feedback on |

|

|

✖ |

Find more details, refund policies and answers to common questions in the Help center.